As many people probably know Santa Claus is, at least in part, based on a real life person; St. Nicholas of Myra. Nicholas was born in 280 C.E. in Patara, Lycia (what is today modern Turkey) into a wealthy family. As an adult he became the Archbishop of Myra and became famous for his generosity and numerous miracles.

The two most famous stories about Nicolas tell how he once saved a poor man’s three virgin daughters from a life of prostitution by secretly leaving a bag of gold for each of them three nights in a row. The other story is much darker and relates how during a famine a butcher murdered three youths, cut them up and placed their dismembered parts in a pickle barrel to cure; his intent being to pass off their flesh as ham. Nicholas arrived at the butcher shop, however, and sensed that something was amiss. Discovering the boys’ bodies in the barrel Nicholas then performed a miracle to rival those of Christ himself and revived the dismembered youths, restoring them to life.[1]

Nicholas died in 343 C.E. on December 6th and was buried in a modest tomb in Myra. In 540 an ornate basilica was built over Nicholas’ tomb but in 1087 Italian merchants broke into the tomb and spirited Nicholas’ remains off to Bari, Italy where they still reside to this day.

That same year (1087 C.E.) the Roman Catholic Church also officially granted Nicholas sainthood and bestowed upon him the title of patron saint of children, sailors, fishermen, merchants, repentant thieves, pawnbrokers, archers and pharmacists. He was also granted the impressive title of “Supreme Controller of the Winds.”

As a saint, Nicholas’ fame grew quickly and he soon became the most popular figure in all of Christendom, right behind Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary. In France and Germany alone two-thousand churches were dedicated to him while another four hundred were consecrated under his name in England. In America St. Nicholas was named the patron saint of New York City in 1809.

Because of his reputation for generosity and gift giving Roman Catholics began exchanging gifts on December 6th, St. Nicholas’s feast day (the anniversary of his death). However, during the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648) Martin Luther, in an attempt to abolish the veneration of saints, moved the day of gift giving from December 6th to December 25th (Christmas Day) and attempted to replace St. Nicholas with the Christ Child, a substitution which did not last.

The MythAs St. Nicholas’ fame as a yuletide gift giver spread throughout Europe his image and story began to synchronize with other similar characters one of the most important of these being England’s Father Christmas.

Also known as King Christmas, Sir Christmas, or Old Christmas the character of Father Christmas dates back at least as far as the 14th-Century, though many folklorists argue that the tradition goes back even further to pre-Roman times and the Druids. Father Christmas is traditionally depicted as an elderly man with a long white beard, dressed in robes with a crown of holly on his head. He is seen riding either a donkey or a goat; animals traditionally associated with pagan fertility rituals. In exchange for gifts English children would leave Father Christmas an offering of mince pie and alcohol.

In England Father Christmas’ presence denoted a time of great feasting and merrymaking, complete with rowdy drunken behavior. Such behavior incensed England’s Puritan denizens who in 1644, upon seizing control of Parliament, officially outlawed Christmas. It would be sixteen years before King Charles II would finally restore Christmas as a national English holiday and usher in the return of Father Christmas.

Though Father Christmas and St. Nicholas would eventually merge in 19th-Century America helping to give birth to the character of Santa Claus, England would nevertheless still retain their traditional gift giver who, as it turns out, stands apart from jolly old St. Nick quite well in having a much more fiery and combatant nature. Examples of this can be found in both J.R.R. Tolkien’s

The Father Christmas Letters (1920-1942) and C.S. Lewis’

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (1950) which feature Father Christmas battling goblins and handing out weapons respectively.

Further north in Holland the legend of St. Nicholas arrived via the Spanish (In fact to this day children in Holland are told that St. Nicholas hails from Spain not the North Pole). The Dutch called St. Nicholas by the name of Sinterklaas and depicted him as a bishop dressed in long robes, riding a magical white flying horse and distributing presents with the help of a Moorish assistant named Zwarte Piet (

Black Peter).[2]

When Dutch immigrants came to America they brought Sinterklaas with them where 19th-Century American children slurred the name into the familiar Santa Claus. The first written mention of Santa Claus in America comes from famed author Washington Irving (

Rip Van Winkle,

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, etc…) who in 1809 described Santa Claus as a Dutch burgher, flying over rooftops in a horse drawn wagon dropping presents down chimneys.

In 1821 a children’s book by an anonymous author featured what is recognized as the first modern depiction of Santa Claus, showing a fur clad man with a white beard driving a sleigh pulled by a single reindeer over a snowy rooftop. Where this image came from is one of the great mysteries of modern folklore.[3] Nevertheless the following year this image was codified with the writing and publication of Clement C. Moore’s famous poem

A Visit from Saint Nicholas, better known today as

Twas the Night Before Christmas.

Following the publication of Moore’s poem the popularity of Santa exploded amongst American children. Popular depiction of Santa from this time – the most famous being those of political cartoonist Thomas “Nasty” Nast – mostly kept inline with the poem’s description. One issue that was left up to the artist’s imagination, however, was what color was Santa’s fur suit. Early color depictions usually rendered it brown, this being a logical color for fur, but it was soon decided that this was too boring a color for a figure as lively as Santa Claus who soon found himself dressed in blue, black, white, orange and purple furs. Green and red fur suits were particularly popular and in the 1940s soda-pop manufacture Coca-Cola officially decided, via a series of popular ads, that Santa Claus’ colors should be red and white; the same colors as those used by the Coca-Cola Company itself.

The Monster

The MonsterIn the 6th-Century in Austria, St. Nicholas was given his first sidekick. No not loveable toy making elves but

Krampus, a shaggy demon with curled horns, a long red tongue and a talent for punishing naughty children with switches and chains. Like St. Nicholas the popularity of this Christmas devil soon spread and became a part of holiday traditions in Austria, Switzerland, Bavaria, Slovenia, western Croatia and Italy. In Germany Krampus became Knecht Ruprecht or “Black Rupert.”

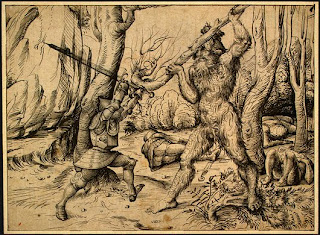

Such Christmas monsters were likely inspired by old pre-Christian legends which told of dangerous Bigfoot-like beasts known as

wild-men who roamed the dark winter nights searching for children. Researchers like Phyllis Siefker and Jeffrey Vallance have argued that today’s Santa Claus has much more in common with these mythical wild-men of Europe than with the Christian saint whose name he uses. Vallance has even pointed out that the name Nicholas may not actually be derived from the saint at all but rather from Nikolas; a 19th-Century colloquialism for the devil.

Part of Siefker and Vallance’s argument rests on the fact that Krampus and his kin failed make it across the Atlantic and into American Christmas tradition. So where did they go? The answer is that like Sinterklaas and Father Christmas, Krampus was absorbed into Santa Claus. Indeed, beginning in the late 19th-Century (1880s and especially 1890s) depiction of Santa Claus began showing the gift giver performing various Krampus-like acts including not only threatening children with switches but in two remarkable illustrations stuffing a (presumably) naughty child into his sack (to carry off who knows where?) and in another beating a child tied to a tree!

Siefker and Vallance also argue that the amalgamation of the Krampus further explains Santa’s furry outfit. Both Sinterklaas and Father Christmas where always traditionally depicted wearing long robes, so the fur must have come from shaggy old Krampus.

ConclusionIn conclusion one can see that the figure of Santa Claus truly is a complex and multifaceted character. So now that I’ve said my piece about him I strongly encourage readers to go out and learn more about Santa in his many and various forms. I promise you won’t be disappointed.

Pictures At Top: Santa, we hardly know thee.

Second down: A statue of

St. Nicholas with the Three Boys in the Pickling Tub. South Netherland, c.1500.

Third: An Eastern Orthodox icon of St. Nicholas.

Fourth: England’s Father Christmas riding a goat.

Fifth: In Amsterdam, Sinterklaas rides into town on a white horse to distribute presents with the help of his Moorish assistants.

Sixth: One of Thomas Nast’s famous drawings of Santa Claus (1881)

Seventh: In the 1940s Santa Claus had his first run in with American consumerism, and it forever changed his life.

Eighth: This German Christmas card shows St. Nicholas and his demon lackey Krampus at work, carrying toys to good children while carting off the bad ones.

Ninth: This giant statue in Lapland depicts the countries' heraldic Wildman. With his red skin, white beard and green leaf garb he looks an awful lot like Santa and is, in fact, probably an ancestor of his.

Last: With Krampus having failed to make it across the Atlantic it was now up to Santa to become the source of both yuletide rewards and punishments as this card from 1907 shows.

Sources and Additional Information (Partial List):Fertility Goddesses, Groundhog Bellies & the Coca-Cola Company: The Origins of Modern Holidays ( 2006) by Gabriella Kalapos

, Spirits, Fairies, Leprechauns, and Goblins: An Encyclopedia (1996) by Carol Rose

, The Encyclopedia of Saints (2001) by Rosemary Guiley

, Christmas Curiosities: Odd, Dark, and Forgotten Christmas (2008) by John Grossman

, Santa Claus, Last of the Wild Men: The Origins and Evolution of Saint Nicholas, Spanning 50,000 Years (2006) by Phyllis Siefker,

Santa is a Wildman! (2002) and

Lapp of the Gods (2005) by Jeffrey Vallance

________________________________________________________

[1] In France the character of the murderous butcher went on to become a traveling companion of St. Nicholas known as Le Père Fouettard (

Father Spanky).

[2] Traditionally Zwarte Piet is always portrayed in live parades by a caucasian actor (or actors) dressed in stereotypical Moorish clothes and donning a wig and blackface (See photo number five). As one can imagine this concept is far from uncontroversial in the Netherlands today and is seen by many black citizens as racially insensitive and an open endorsement of slavery. In 2006 attempts were made to substitute the traditional Zwarte Piet with a less racially offensive one. Public outcry however saw the return of the traditional Zwarte Piet the following year and in 2008 the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven canceled a planed exhibit on the racial implications of the Zwarte Piet character after receiving numerous death threats.

[3] Of particular interest to many folklorists is the question where the reindeer motif originated. Some researchers have suggested a connection between Santa’s flying reindeer and the flying reindeer in Siberian shamanism, though this seems to be a bit of a stretch.